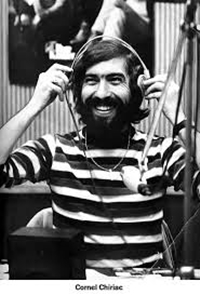

Cornel Chiriac’s cultural opposition to the communist regime in Romania is related to his underground activities as a jazz critic and author of a samizdat about this musical genre, as well as his official activities as a radio producer at Radio Romania (the Romanian official radio station) and then at Radio Free Europe. Due to his extremely popular musical show Metronom, which he initiated in Bucharest and continued in Munich after his emigration, Cornel Chiriac had an enormous influence upon the younger generation at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s.

The Romanian secret police, the Securitate, monitored him closely from 1963 until his untimely death in 1975. His surveillance created a substantial corpus of documents relating to his activities and his interactions with his fans. Out of the five main fonds of the archives of the former Securitate, which correspond to its operative interests and bureaucratic rules, the documents in the Cornel Chiriac Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS can be found in four: the Documentary Fonds, the Informative Fonds, the Network Fonds, and the Fonds of the Department of External Information. Two major types of documents are included in this ad-hoc collection. On the one hand, there are documents created by the Securitate, which collected information about Cornel Chiriac and his family in informative notes or phone calls transcripts, and devised plans of action against him. On the other hand, the Cornel Chiriac Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS comprises letters which were sent to him after his emigration to the Federal Republic of Germany, when he was a radio producer in the Romanian section of Radio Free Europe. These letters were intercepted on their way to Munich by officers of the secret police, and thus are now in the Securitate archives. However, many of the letters sent from Romania did reach the editorial office of Radio Free Europe. Cornel Chiriac was one of the persons whom the secret police continued to keep under surveillance even after his emigration. Moreover, rumours say that his murder in 1975 was orchestrated by the Securitate, although this has obviously never been proved.

It was a passion for jazz that pushed Cornel Chiriac to disseminate information about this musical genre among the Romanian audience through a samizdat produced under the title Jazz Cool. It was this kind of illegal activity which initiated his surveillance by the Securitate in October 1963. In communist Romania, jazz music was considered decadent and promiscuous, an icon of the capitalist world and a subversive musical genre associated with the United States. As the authorities concluded that this musical genre had a negative influence among young people, who ought to take inspiration from communist revolutionary principles and not from the rebellious capitalist spirit, access to jazz music or sources of information about jazz culture was very limited. Although not explicitly banned, ths kind of music was mostly listened to on foreign radio stations. Moreover, after the short period of liberalisation at the end of the 1960s, the very mentioning of the word “jazz” was tacitly eliminated from radio and television shows, from publications and on vinyl records labels, since it was obviously foreign and thus in conflict with Ceaușescu’s anti-Western Theses of July 1971 (Stratone 2017, 25). Implicitly, listening to jazz or collecting records with such music might have been a source of serious troubles.

As a great fan of jazz music since his adolescence, Cornel Chiriac tried his best to spread information about this kind of music among his Romanian audience, making use of his extensive knowledge in the field, which he acquired from foreign broadcasting agencies. His favourite show was Willis Conver’s Music USA – Jazz Hour, a musical programme that Voice of America started to broadcast worldwide in 1955. Additionally, Cornel Chiriac read the few foreign magazines that reached Romania. Among them, there was a Polish periodical entitled Jazz, which featured articles about this genre of music. This was turned, with the help of a Polish-Romanian dictionary, into his main source of information regarding the international and local variants of jazz (Udrescu 2015, 63, 67). Given the scarcity of information about jazz music in Romania, Cornel Chiriac decided in 1961 to self-publish a hand-written magazine about this musical genre. The publication was called Jazz Cool and contained up-to-date references about the discography of jazz artists and bands, music charts published by foreign magazines, information about jazz concerts and festivals organised around the world, etc. Everything in Jazz Cool, from the layout of the text to the illustrations, was authored by Cornel Chiriac. This samizdat was usually “issued” in maximum ten hand-written copies, thanks to his friend Mircea Udrescu who helped him to multiply the featured items manually. Apart from editing Jazz Cool, Chiriac’s status as a jazz connoisseur was enhanced after he managed in 1963 to publish a critical article about the musical orchestra of Pitești in the above-mentioned Polish periodical Jazz (Udrescu 2015, 52, 63–67, 103).

However, it was Cornel Chiriac’s authorship of Jazz Cool that brought him the unwanted attention of the Romanian secret police. The Securitate began its investigation into the hand-written magazine in Bucharest, and not in Pitești, where Chiriac resided at that time. The motive was that a copy of Jazz Cool had appeared in the student milieu in the Romanian capital. Following information received from a source, the Securitate extended its investigation to Pitești in September 1963 and identified Cornel Chiriac as the editor of the jazz magazine at the end of October. Consequently, on 31 October 1963 the Securitate opened a so-called informative verification file (dosar de verificare informativă) on his name (ACNSAS I 204265, vol. I, ff. 136–138, 22–25). Its purpose was to verify the information provided by the informers and to collect the necessary evidence of the illegal activities of young Chiriac. Until 5 August 1964, when he was interrogated by the Securitate, his correspondence, moves and meetings were closely monitored by the local branch of the Securitate and its informers. Apart from informative notes and copies of the letters sent and received by Cornel Chiriac, the documents created by the Securitate between October 1963 and August 1964 also contained a plan of measures aimed at collecting as much information as possible about him and his activities of cultural dissidence. All the documents testified to his passion for jazz music, his plans for publishing abroad another article about jazz in Romania, and his contacts with musicians in Bucharest to whom he sent copies of Jazz Cool (ACNSAS I 204265, vol. 1; Udrescu 2015, 68–78). On 5 August 1964, the Securitate searched his house, confiscated all the copies of the Jazz Cool magazine and interrogated him at its local headquarters in Pitești. As the son of an activist of the communist party, Cornel Chiriac was only given a warning and he had to sign two declarations that he would stop any kind of activity which could interfere with the communist “social order.” He acknowledged his guilt of illegally publishing the Jazz Cool magazine and took all the responsibility for its creation and circulation in order to save his friends who had also been involved in this enterprise (ACNSAS I204265 vol. 1, ff. 130–131; Udrescu 2015, 78–79). These documents then became part of his informative surveillance file (dosar de urmărire informativă).

In the same year, 1964, Cornel Chiriac moved to Bucharest and the next year he began to work as a producer of the musical show Metronom for the national radio station, Radio Romania. Taking advantage of the liberalisation in the first years of Ceaușescu’s leadership of the Romanian Communist Party, he broadcast the newest pieces of jazz, rock and folk music. By carrying on his job at the radio station, Cornel Chiriac turned into an epitome of the cultural nonconformism of the younger generation, which faithfully listened to his really outstanding musical show in comparison to the usual offer in the Romanian mass media of that time (D. Ionescu 2016, 26–32, 34). Cornel Chiriac’s cultural activities which conflicted with the official views of the communist regime also included the organisation of a series of conferences about jazz artists or styles at the Students’ House of Culture in Bucharest (Udrescu 2015, 93). Above all, his opposition manifested in his repeated and successful bypassing of the official censorship at Radio Bucharest. Every producer had to record the show in advance in order to get approval. Chiriac, however, managed to switch tapes before going on the air and broadcast stuff that had not received clearance in advance. Obviously, the Securitate continued to monitor Cornel Chiriac even after his move to Bucharest in 1964. His file contains transcriptions of his telephone calls, intercepted correspondence, and informative notes. Covering the period between 1964 and 1969, the documents trace his contributions to the conferences at the Students’ House of Culture in Bucharest and his contacts with Romanian musicians and foreign citizens (Udrescu 2015, 94-95, 122-126).

It is particularly interesting that, due to Chiriac’s frequent meetings with foreigners and especially foreign diplomats, the Securitate became interested in October 1965 in using him as source of information. His network file (dosar de rețea) contains informative notes and summaries of his declarations about his contacts with foreigners, including foreign diplomats, from whom he borrowed vinyl records of jazz music for his radio shows and jazz conferences. There is no doubt that the Securitate managed to use Cornel Chiriac as a source of information about these foreigners. However, the information he delivered, mostly about their collections of vinyl records, was of no interest to the secret police, so they decided to abandon him as a source (ACNSAS R309386, ff. 1–57).

Until 1969, when he left Romania permanently, Cornel Chiriac became the most important radio and music producer in the country. He can arguably be considered a founding father of the Romanian jazz, rock, and folk culture of the late 1960s. Disappointed by the increasingly suffocating censorship, Chiriac took advantage of a tourist visa he had received and emigrated from Romania in 1969. Soon after, he resumed his music show Metronom at Radio Free Europe and started to produce other musical programmes (D. Ionescu 2016, 40–41, 47, 61). Until his violent death in 1975, his music broadcasts represented the main window opened to Western culture that was available to the Romanian youth. The Securitate continued to collect information about Cornel Chiriac even after he had fled the country in 1969. This is hardly surprising considering that he used his music show at the Romanian desk of Radio Free Europe to harshly criticise the communist regime and its leader (Măgură-Bernard 2007, 26–27). The documents covering Chiriac’s exile were included in his informative file with the codename Jak (sic!) (ACNSAS I204265, vol. IV), and in the file created by the external branch of the Securitate, the Department of External Information (Udrescu 2015, 127, 135, ACNSAS SIE32297). Information was collected as result of a complex surveillance operation devised by the Securitate in Pitești, where Cornel Chiriac’s parents and relatives were permanently under surveillance, and in Munich, where the Securitate monitored his activity with the help of those visiting him there. These documents mainly consist of informative notes, transcriptions or summaries of telephone conversations between Cornel Chiriac and his parents and relatives, or personal conversations recorded in his parents’ house. Cornel Chiriac’s violent death on March 4 1975 due to a stab wound ended the surveillance process and the collection of information about him in his Securitate file.

An appendix to this collection are the letters sent from Romania to Cornel Chiriac while he was at Radio Free Europe. These letters must be taken as part of this ad-hoc collection even if they are not a part of Cornel Chiriac’s personal file. Most of these letters can be found in the Documentary Fonds of the former Securitate, a different category of files, which had an educational purpose for the officers of the secret police. Every county in Romania had a documentary fonds that included the following topics of surveillance: Culture and Art, Youth and Education, Religions and Sects, Industry, Health, Activists of the Former Political Parties, Foreign Tourists, etc. The letters to Chiriac can be found in the Youth and Education section of these documentary fonds. These are letters that were intercepted by the Securitate and never reached Radio Free Europe. The secret police managed to collect thousands of letters sent by young people who asked for musical dedications or for “a good thought from Cornel” – as they put it – to be sent during the Metronom show. Listening to this foreign radio station constituted a source of troubles and as result, many young people received warnings from the Securitate for sending these letters.

After the fall of the communist regime, the files created by the Securitate about Cornel Chiriac were inherited by the SRI (Romanian acronym for the Romanian Intelligence Service), the Securitate’s successor institution. From 2000, the SRI began the transfer of the Securitate documents to the newly created CNSAS (Romanian acronym for the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives). The Securitate files regarding Cornel Chiriac have been accessed by researchers, journalists, and some of his closest friends. Documents from these files have been partially published in the volume Metronom ’70: Cornel Chiriac în documentele Securității (Metronom ’70. Cornel Chiriac in the Securitate documents) by Cornel Chiriac’s best friend, Mircea Udrescu.