The writer, essayist, and art historian László Cs. Szabó, who lived in Kolozsvár (today Cluj, Romania) as a child and in Budapest as an entrant regularly confronted dictatorial and authoritarian regimes in his life. In the 1930s, as the head of the Literature Department of the Hungarian Radio, he provided a forum for left-wing writers, and helped some of his intellectual-mates (for example Miklós Radnóti or István Vas), who had gotten into trouble due to the discriminatory Jewish laws, by giving them translation work. In 1944, protesting the German occupation of Hungary, he resigned from the chief position at the Radio and retreated from public life. After the war had come to an end and before the communist takeover, he taught at the Academy of Fine Arts. But Cs. Szabó, fearing the increasing power of the Hungarian Workers’ Party, decided to stay in Rome after his half-year scholarship in February 1949 (when the Mindszenty trial was taking place in Hungary). In other words, he chose immigration. In 1951, he moved to London, where he worked at the BBC until his retirement. In his radio program and writings, Cs. Szabó criticized the cultural policy and actions of the Rákosi and the Kádár regimes. As a Hungarian man of Transylvanian origins, he complained that the Hungarian government did little to help the Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin. Additionally, he pointed out that the Hungarian leadership forbade or censored classic and modern Hungarian literature, because of the ‘sensibility of the peoples of the neighboring socialist countries.’ Moreover, he published poems in Britain by those Hungarian poets, who were unnoticed for years after 1949 (for example Sándor Weöres, János Pilinszky and Ágnes Nemes Nagy). In 1956, he stood his ground in support of the Revolution and condemned the Soviet occupation of the country.

Moreover, László Cs. Szabó participated actively in linking Western Hungarian emigration. He played a decisive role in shaping Hungarian literature in the West after 1945. He was acclaimed by his own generation and the younger immigrants as their personal guide and a person of great knowledge. With his friends Zoltán Szabó and István Borsody, he founded the Horizon Friend Company to promote the periodical Horizon (Látóhatár), which was created by young immigrants. Soon, they managed to raise money to cover the cost of publishing this appealing bulletin, which was published in print beginning in 1953, and it soon became one of the most important Hungarian periodicals in the West. Cs. Szabó regularly wrote in this periodical and in “Hungarians” (Magyarok), “Literary News” (Irodalmi Újság), and “The Catholic Review” (Katolikus Szemle). Cs. Szabó also took part in the work of Hungarian emigrant organizations. In 1964, he was the first lecturer at the Szepsi Csombor Circle. He followed the publications and lectures of the Mikes Kelemen Circle and the Hungarian Evangelical Youngsters Abroad, and he was a founding member of the European Protestant Hungarian Free University in 1969. Later, he became a member in the syndicate and curatorship of this organization. Between 1972 and 1975, he was a member of the presidency of the Free University, and in 1975 he was elected eternal honorary president.

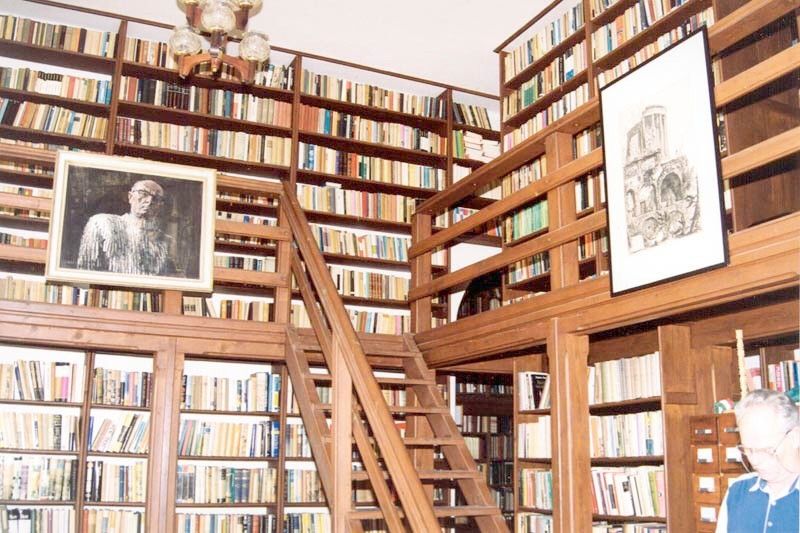

The original library of László Cs. Szabó, which contains 9,000 books, was dispersed or lost after his emigration. In 1949, Cs. Szabó decided abruptly to emigrate when he was in Rome, so he was unable to bring his original collection to the West. He decided never to create another large collection. He only bought encyclopedias, dictionaries, and reference books which were necessary for his radio job. However, after a few years had passed, he had compiled another private library with thousands of books in his apartment at London. The bibliophile László Cs. Szabó collected books all his life. He believed this was a requirement for someone who wanted to belong to European culture. Moreover, his library helped him play a mediator role as someone who united the intellectual life of the emigrants. Part of his library helped Cs. Szabó in his work as a kind of a reference library, but it was also a spiritual workplace and a refuge for him. Literary historian Lóránt Czigány helped him buy and collect the books. Czigány also moved to England after his emigration. In the first years, Cs. Szabó mainly bought world literature and art books. Works by contemporary Hungarian writers could only reach Cs. Szabó in larger quantities after 1956 thanks to the détente and the increasing East-West cultural transfer. At the time, some friends of Cs. Szabó (for example Áron Tamási, István Vas, Sándor Weöres, Gyula Illyés, János Pilinszky, and others) sent him their own books.

The library of László Cs. Szabó was one of the most important centers of Hungarian literature in the West. It was a huge asset in Hungarian intellectual life that this uniquely rare and rich collection was moved to Hungary. The “rediscovery” of Cs. Szabó started after the further easing of international tensions: in 1979, after 30 years of emigration, one of his writings (

The Diary of Dickens) was published in Hungary. After this, in the Autumn of 1980, at the invitation of Gyula Illyés, for the first time since 1948 he stepped on Hungarian soil, and later he delivered a lecture at his former workplace, the Academy of Fine Arts. After that, until his death, he regularly visited Hungary, but he could not travel to his real native land, Transylvania. He always thought his real home was Kolozsvár (Cluj), which was a famous university town, like Sárospatak, which was proud of the Calvinist college he had attended. Sárospatak was familiar and homelike for him. Personal memories connected him to the town: between 1945 and 1948, he annually visited this little town in northeastern Hungary, much as he then did in his last years. So, as he requested in his last will and testament, he was buried in the Calvinist Cemetery of Sárospatak, and he bequeathed his library to the Scientific Collections of the Calvinist College of Sárospatak. The collection was transferred from London to Sárospatak in August 1985. Professor Kálmán Újszászy, former diocesan main administrator west of the River Tisza, and György Benke, director of the main collections at the time, played major roles in preserving and transferring the collection.