Vinko Nikolić was born in Šibenik, in southern Croatia on 2 March 1912. He was a writer, poet, journalist, literary critic and publicist, one of the most prominent Croatian émigré intellectuals. He was raised in a poor and large Catholic family. He attended primary school and the classics gymnasium in Šibenik and studied the Croatian language, Yugoslav literature, Croatian history, and the Russian and Italian languages from 1932 to 1937. Due to his political opposition to the Yugoslav regime, he did not succeeded in finding employment immediately. Initially he worked as the prefect of Archdiocesan convictus in Sarajevo. After the establishment of the Banovina of Croatia, he found employment in Zagreb and he lectured as an assistant professor at the Commerce Academy from 1939 to 1943. He organized the semi-monthly review Life for Croatia in 1942. In the last two years of the war he was a professor at the First Boys’ Classics Gymnasium in Zagreb. After the collapse of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Nikolić became involved in the public life of the Independent State of Croatia, where he dealt with issues of culture and propaganda for the Ustasha regime. He simultaneously advanced in the military hierarchy of the Ustasha movement, where he attained the reserve rank of lieutenant and later captain.

After the downfall of the Independent State of Croatia, he first left for Austria, and later went to Italy. In 1946, he jumped off of a train to avoid deportation to communist Yugoslavia by the Allies in Italy. After that. he began writing a doctorate in Slavic linguistics in Rome on the theme of Croatian modern poetry under the tutelage of Prof. Giovanni Mavere. But he fled from Italy via France to Argentina due to the permanent threat of extradition to Yugoslavia. In Argentina, he began to work as a journalist, so he edited the journal Hrvatska with Franjo Nevistić from 1947 to 1950. In the following year, together with Antun Bonifačić Nikolić initiated the Croatian Review, the core activity of which was the promotion of anticommunism. Later, it became one of the most important and influential Croatian émigré journals, in which many emigrants of different political and ideological orientations collaborated.

During his life in an emigrant, Nikolić distanced himself from Ante Pavelić and the Ustasha regime, and together with his associates Bogdan Radica and Jure Petričević, his writings were critical of the Ustasha movement. In polemics with Vjekoslav Vrančić in 1969, Nikolić clearly stressed his renunciation of Ustashism. "It may be stated that people already today will surely not accept either the Ustasha or any other totalitarian ideology and its leadership as the foundation and support of the future constitution of Croatian state" (Nikolić, Vinko. "The future cannot be built on Ustasha policies ," Croatian Review 1969. no. 1-2, 144). His political vision was an independent and democratic Croatian state, free from every ideology and historical burden. He additionally advocated for the historical reconciliation between communists and nationalists after the experiences of civil war in Croatia (1941-1945). To possess Nikolić's review was illegal, and Nikolić's other works were also forbidden. The reason was his critical stance against communism and the Yugoslav ideology. Nikolić began publishing works as part of the Library of Croatian Review, in which he edited and printed 65 books on different topics, written by Croatian émigré intellectuals.

Nikolić returned to Europe in 1966, to France, where he planned to continue publishing his review in order to exert greater influence on the situation in the homeland. The intervention of the Yugoslav embassy in Paris forced the French government to take action, and the French authorities seized and destroyed an issue of the review and expelled him from France. Nikolić addressed President De Gaulle and Culture Minister Andre Malraux with an appeal to allow his activities in their country. After travelling throughout Europe, from London, Munich, Salzburg to Zurich, he settled in Spain, where he continued his émigré and publishing work in Barcelona from June 1968 onward.

Nikolić and the circle around Hrvatska revija supported the Croatian Spring, a reform movement of the Croatian communists, and especially the Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Literary Language in 1967, which opposed the regime's forcible linguistic unitarism. His review was read by the Croatian Marxist intelligentsia in the country at the time of the Croatian Spring. Although a Catholic, Nikolić criticized the Protocol of 1966 which regulated anew the relations between the Holy See and Tito's Yugoslavia after the communist regime had unilaterally terminated them in 1952. He protested when the communist leader visited Vatican for the first time in 1971, when Pope Paul VI met Tito. He considered Vatican's concessions to Yugoslavia as a move against the Croatian national question. In 1973, he was awarded compensation by a French court due to his expulsion in 1966.

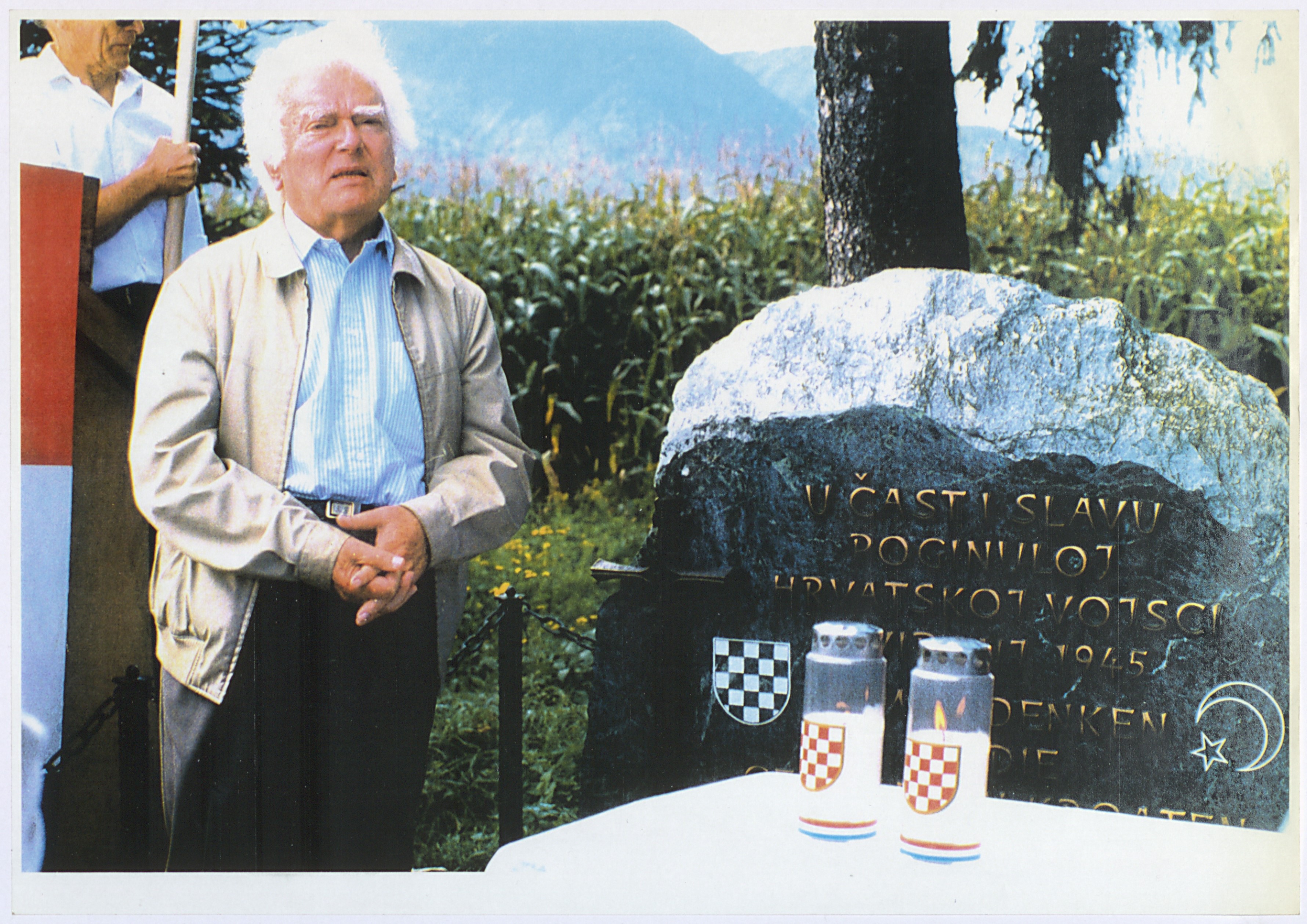

Nikolić returned home after 45 years of life in exile, after the communists lost power in the first democratic elections in Croatia in the spring of 1990. In 1991, he definitively moved to Croatia, where he lived until his death in his native city of Šibenik on 12 July 1997. He supported the new president, Franjo Tuđman, and his Croatian Democratic Union and the process of Croatia’s separation from Yugoslavia. In the last years of life Nikolić was a representative of that party in the Croatian Parliament as of 1993, the head of the Croatian Heritage Foundation (1992-1993) and the vice-president of Matica hrvatska.

Nikolić was the author and editor of several books, numerous collections of poems, essays and articles. His most important books were At the Door of the Homeland. Encounters with Croatian Emigration in two volumes in 1965 and 1966, followed by The Tragedy of Bleiburg in 1977 and Stepinac is His Name in 1978. All of these books were banned by the regime because they criticized the circumstances in Croatia and Yugoslavia under communist rule. In his émigré period, Nikolić corresponded with many members of the post-war Croatian emigrant community (Bogdan Radica, Jure Petričević, Jere Jareb, Ante Smith Pavelić, Ivan Meštrović, Mate Meštrović, Karlo Mirth, Vladko Maček, Filip Lukas, Luka Brajnović, Stjepan Buć, Jure Prpić, Tihomil Rađa, Ivo Rojnica, Stjepan Sakač, Gvido Saganić, Bruno Bušić, Ante Ciliga, Lucijan Kordić, Krunoslav Draganović, Tihomil Drezga, Vladimir Ciprin, Rajmund Kupareo, Nikola Čolak, Ante Kadić, Jakša Kušan, Zlatko Markus, Luka Fertilio, Franjo Hijacint Eterović, Marko Čović, Antun Bonifačić, Vinko Grubišić, Milan Blažeković, Hrvoje Lorković and others).

After returning to Croatia in 1991, Nikolić and his wife Štefica handed over his entire manuscript collection and literary legacy to the National and University Library in Zagreb. It consists of numerous books and newspapers printed abroad, his manuscripts, the archives of Croatian Review, his correspondence with many important people of that time. Part of his legacy (manuscripts, correspondence and the archives of Croatian Review) is held in the Manuscript and Old Book Collection.

The newspaper materials became part of the Periodical Reading Room and the books became part of the Foreign Croatica Collection. His stance on the culture of the written word and materials testify to his oppositional activities, which Nikolić confirmed by keeping these materials and storing them in Croatia’s largest library.

Željka Lovrenčić, the head of the Foreign Croatica Collection, notes that all of Nikolić's activities in the diaspora can be described as cultural opposition: “You could say that his life outside of Croatia was genuine cultural opposition. Opposition made evident by the books, words, culture – for you to show, in a particular environment that was not so friendly to Croatians. (...) What these people went through in Argentina – is just horrible. All the while they managed to preserve that spirit and culture – that was the real opposition.”