Cornel Chiriac (real name Ionel Corneliu Chiriac) was a Romanian journalist, jazz drummer, and radio and record producer, who worked for Radio Romania and Radio Free Europe (RFE). He was born on 9 May 1942, in Uspenca/Uspenivka (now in Ukraine). Later, his parents moved to Pitești, a city approximately 100 km northwest of Bucharest. Despite the fact that his parents were “intellectuals” (both were teachers), Cornel Chiriac was officially considered a person with a “healthy social origin.” His father, nicknamed “the Marxist,” was a member of the Argeș regional committee of the Romanian Workers’ Party (the official name of the communist party in Romania between 1948 and 1965) and the editor-in-chief of its official publication Secera și ciocanul (The hammer and sickle). His father’s membership of the local party elite sheltered the rebellious adolescent Cornel Chiriac from unwanted interventions on the part of the authorities. It also provided him with access to goods and financial resources unavailable to the rest of the population, which allowed him to buy a camera and a radio for listening to foreign radio stations. In short, he was one of the few privileged young people who could pursue his many hobbies, which included music, acting, painting, photography, and poetry (Udrescu 2015, 16–29, 195).

Cornel Chiriac’s most enduring passion was jazz music, to which he dedicated his entire life. He started to be interested in this musical genre in the middle of the 1950s, when jazz was still identified as a Western cultural product that allegedly undermined the “correct” education of Romanian youth. Thus, Chiriac joined the cultural cold war and took the side of the West in this cultural competition once he began listening to foreign radio stations, especially Voice of America (VOA). His favourite show was Willis Conver’s Music USA - Jazz Hour, a musical programme that VOA started to broadcast worldwide in 1955. For Cornel Chiriac and other young people in the Eastern bloc, Willis Conver’s daily jazz programme was the main source of knowledge about this musical genre and a glimpse into the West and the American lifestyle (Ritter 2016, 13). The adolescent Cornel Chiriac also listened to other foreign radio stations which regularly broadcast jazz (Udrescu 2015, 48). During the late 1950s, Cornel Chiriac’s parents were among the few Romanians who could afford to buy a radio receiver. Their price ranged between 400 and 4,000 lei, at a time when the net average national monthly salary varied between 400 lei in 1956 and 750 lei in 1959 (Marin 2016, 671). Over the next few years, with the help of his parents, Cornel Chiriac bought a portable radio receiver and a Belcanto record player to play his vinyl records (Udrescu 2015, 175-176). Another source of knowledge of jazz music was foreign magazines, especially those from Poland that arrived in Romania for the first time at the end of the 1950s. These publications could be legally bought, but the number of subscriptions was limited to two or three for the entire city. Consequently, Cornel Chiriac started to read La Pologne, a magazine published in French, and later the Polish periodical Jazz, which featured articles about the international jazz community. This turned into his main source of information about jazz music, with the help of a Polish–Romanian dictionary (Udrescu 2015, 63, 67).

Cornel Chiriac’s passion for jazz music influenced his decision in 1961 to produce a samizdat, in fact a hand-written magazine about this musical genre. Its purpose was to make jazz music known in Romania and also provide up-to-date information to other Romanian jazz lovers. The samizdat Jazz Cool included discography of jazz artists and bands, charts published by Down Beat and other magazines, articles translated from the Polish periodical Jazz, and information about jazz concerts and festivals organised around the world. The content, the layout of the text, and the illustrations inserted in Jazz Cool were the work of Cornel Chiriac. Jazz Cool was usually “issued” in a maximum of ten copies as his friend Mircea Udrescu helped him to multiply all the featured items. Apart from editing this hand-written magazine, Cornel Chiriac began to work on the Jazz-Cool-Encyclopaedia, a project which he sadly never finished due to his decision to emigrate. His critical article about the musical orchestra of Pitești was published in the Polish periodical Jazz at the end of the year of 1963 and enhanced his status as a jazz connoisseur (Udrescu 2015, 63–67, 103, 52).

His Jazz Cool samizdat magazine brought Cornel Chiriac the unwanted attention of the Romanian secret police, the Securitate. Consequently, in the summer of 1964 the Securitate held him in custody, searched his house in Pitești, confiscated copies of Jazz Cool, and interrogated him. In order to protect his friends who had helped him with the magazine, Chiriac took all the blame for “publishing” it. After questioning him, the Securitate gave him only a warning and released him after he had signed a declaration that he would never again engage in such activities against the “social order” (Udrescu 2015, 77, 81). Even though Cornel Chiriac might not have previously considered his passion for jazz and foreign music as a form of opposition to the Romanian communist regime, the encounter with the Securitate influenced him in consciously pursuing his passion in that perilous direction.

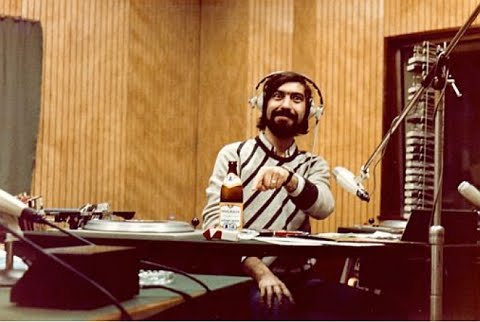

In the same year, 1964, Cornel Chiriac moved to Bucharest and soon began to work for the national radio station, Radio Romania, as the producer of the music show Metronom, which quickly became extremely popular among young people. There he organised a sound archive, recording as many tracks as he could from the albums he had borrowed from friends and acquaintances (including foreign diplomats, jazz artists, and the offspring of the communist nomenklatura) or had bought on the black market. Taking advantage of the ideological relaxation and liberalisation in the first years of Ceaușescu’s rule, during his show Metronom, he broadcast the latest jazz, rock, and folk music. Thus, he became an epitome of cultural opposition by working inside a Romanian institution. According to one of his many listeners, Cornel Chiriac became an idol for them as he not only broadcast the latest musical tracks, but also educated his audience about how to listen to music, value it, and talk about it. Chiriac took a great interest in Romanian rock bands and brought some of them to Bucharest to illegally record their songs in the studios of Radio Romania (Ionescu 2016, 26–32, 34). In addition, Cornel Chiriac was involved in the organisation of a series of conferences about jazz artists or styles at the Students’ House of Culture in Bucharest. His theoretical lectures on jazz were followed by musical performances, some of them by well-known jazz artists and bands of that time (Udrescu 2015, 93).

A rebel by nature, Cornel Chiriac could not stand any form of censorship and used every available opportunity to revolt against it. For instance, after the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, he managed to trick the censor and play in his programme a folk song about one big wolf and five small wolves that attacked a sheepfold. This was a thinly veiled criticism of the Warsaw Pact’s brutal interference in Czechoslovakia to stop the Prague Spring. As Ceaușescu himself condemned the invasion, this action remained without immediate consequences, but it later provided further arguments for his ousting from the national radio station. The last straw in his case was the broadcasting of the Beatles’ song “Back in USSR” during the Metronom programme. Consequently, Cornel Chiriac was fired from Radio Romania in 1969, so he decided to flee Romania the same year (D. Ionescu 2016, 40–41).

Taking advantage of a tourist visa, Cornel Chiriac reached the refugee camp in Treiskirchen, near Vienna. The director of the Romanian desk of RFE, Noel Bernard, found out about his arrival and offered him a job (Morariu 2015). His participation in the cultural cold war against communism entered a new phase. Cornel Chiriac resumed his Metronom show at RFE and also produced several other musical programmes, such as Rock in Concert, By Request, and Jazz à la Carte (D. Ionescu 2016, 47, 61). His music and comments were now blended with criticism against Ceaușescu’s regime and frequent denouncements of the lack of liberty for young people. Cornel Chiriac attracted his loyal listeners from Radio Romania to RFE. Some of them actually discovered RFE due to his musical broadcasts and gradually became faithful listeners of this foreign radio station. Until his violent death on 4 March 1975, Cornel Chiriac continued to receive numerous letters from young people. In their letters, these youngsters described the grim situation in Romania, the tightening of censorship and the reinforcement of ideological control over cultural production and consumption after the so-called Theses of July 1971. They also asked their idol to broadcast their musical preferences, which he always did (Udrescu 2015, 156–157; Măgură-Bernard 2007, 26–28; D. Ionescu 2016, 62). Cornel Chiriac used the radio microphone and his passion for music to create an alternative view of the world for young people in Romania. This was a world which valued freedom, personal choice, diversity in all its forms, and above all moral dignity. While Cornel Chiriac’s broadcasts offered young people a glimpse into the Western world, they also greatly influenced their nonconformism and rebellious attitudes.